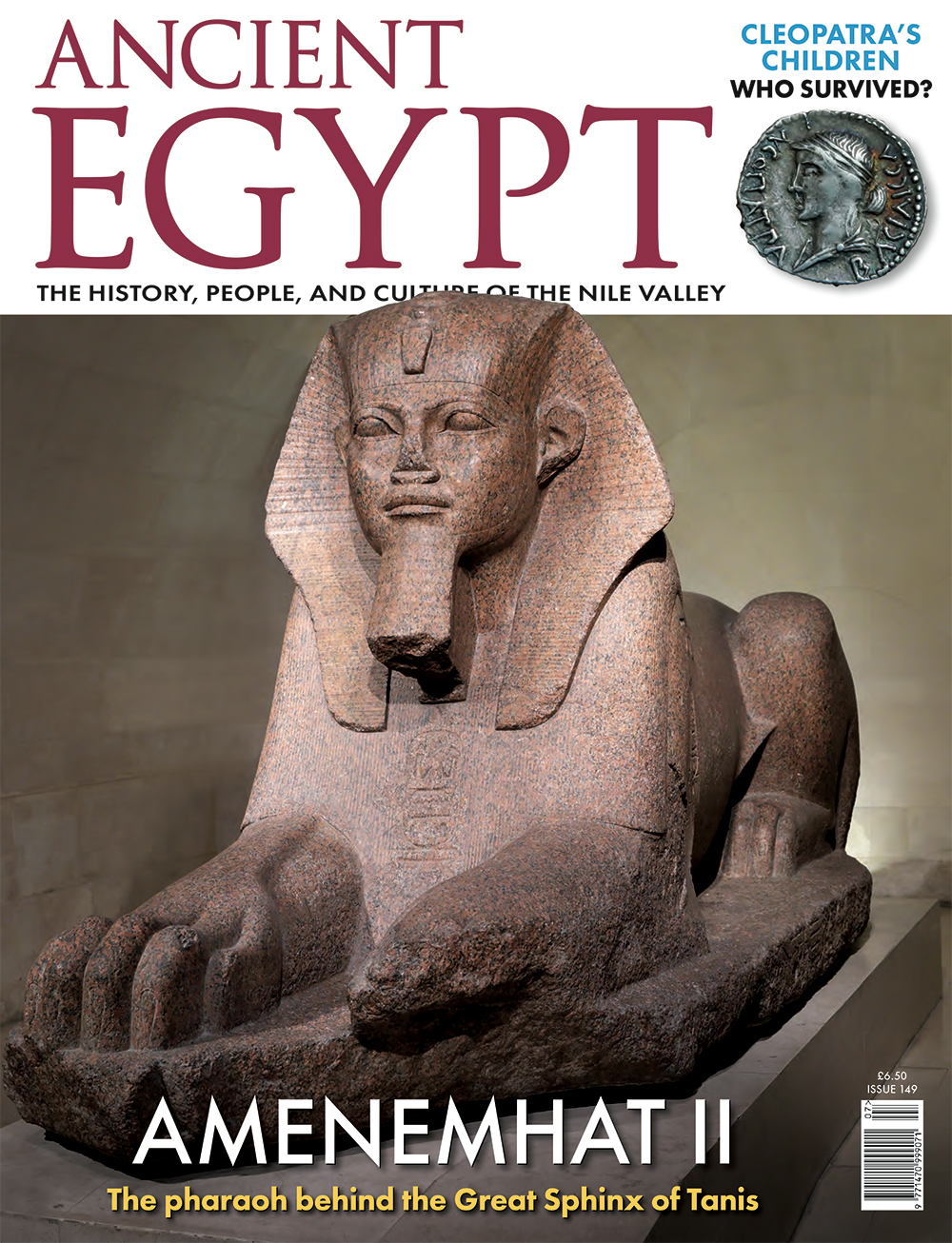

Often the process of recreating ancient Egyptian history can resemble the intricate plot of a detective novel. Many apparently minor discoveries, when pieced together, can form a coherent whole, although sometimes key pieces are missing. Such was the case with the reign of the Middle Kingdom pharaoh Amenemhat II. None of his temples have survived, and his ruined pyramid has not been fully excavated. The only major item bearing his name is the sphinx pictured on the cover of this issue. As Wolfram Grajetzki tells us, very little was known about his reign until parts of his annals, covering two years of his reign, were discovered and eventually deciphered. The largest fragment of the annals, written in a kind of hieroglyphic shorthand, was found on the underside of the base of a statue of Ramesses II carved from a reused block of granite.

But some evidence of Egypt’s past can be hidden in plain view. The mummy of Gebelein Man, popularly known as ‘Ginger’, has been on display in the British Museum for over a hundred years. It was only by chance that a hand-held infrared light was directed at Ginger’s arm and a tattoo suddenly became visible. A whole new branch of Egyptological investigation was opened, looking for, and finding, tattoos on many other mummies in museum collections. Renée Friedman brings us some of the latest findings in this brand-new field of study.

Other articles in this issue cover some other lesser-known areas of Egyptological study: the fate of the children of Cleopatra VII, recounted by Diana Bentley; the Egyptian monuments seen by Aidan Dodson in Constantinople; and the archaeological sites of Mo‘alla and Tod that see very few tourists other than more adventurous independent visitors like Karl Harris.

Hilary Wilson has told us before about the importance of fish in the diet of the ancient population and, in this issue, she concentrates on one particular inhabitant of the Nile – the Nile perch, the ‘King of Fish’.

Andrew Fulton concludes his series studying Ani’s Book of the Dead; Campbell Price studies an unusual bust in Boston Museum of Fine Arts; and Stephanie Boonstra chooses the discovery in 1933 by Ruth Waddington of a(nother) bust of Nefertiti as her ‘Milestone in Egyptology’ – once more an example of a chance discovery that changed our knowledge of the ancient civilisation.