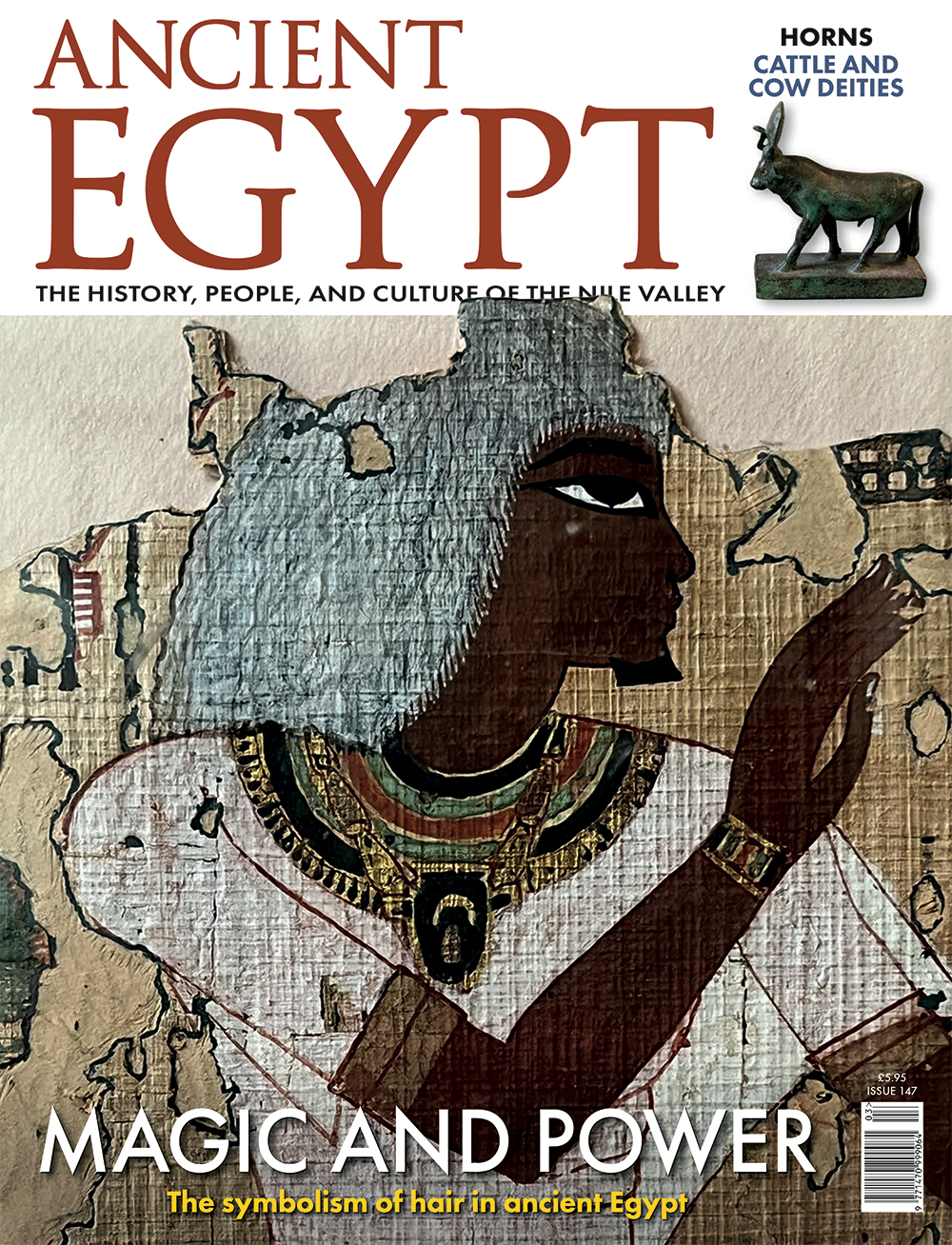

Much time and effort were expended by ancient Egyptians of both sexes in the styling of their hair. Research by Amandine Marshall, summarised by her in this issue, has shown that this was not merely a matter of personal vanity. The ancient Egyptians considered that hair was a vital part of a person’s essence, and had magical properties that could be used for good or evil.

Hopefully, a person would avoid employing such magic for evil purposes; at the end of life, the weighing of the deceased’s heart against the feather of maat, as depicted in the Papyrus of Ani described by Andrew Fulton, would determine whether he could pass into the afterlife or be devoured by Ammit.

Headgear of a different type was used in statues and reliefs of deities, many of which incorporated the horns of cattle, as Hilary Wilson explains in the first of a two-part article on the significance of animal horns.

The most famous artistic depictions of ancient Egyptian scenes are undoubtedly by David Roberts, but readers who are familiar with the monuments he painted will know that he frequently employed ‘artistic licence’ in his works. Lee P Ruddin tells us that the paintings of Robert Talbot Kelly, which have been much neglected, are of equal quality, and are a much more accurate record of the scenes he witnessed.

One monument that Kelly could not paint was the Pharos, the giant lighthouse that stood in the harbour at Alexandria – it was destroyed by an earthquake 700 years ago – but there are many depictions of its presumed appearance. Andrew Michael Chugg has studied these and a wide variety of sources to create an accurate reconstruction with astonishing features.

We are familiar with the series of articles by Karl Harris describing various sites he has visited by car or taxi. Now, for the first time, he hires a bicycle to make an excursion from his West Bank hotel in Luxor to the Birket Habu and some rarely visited nearby monuments.

The lives of three pharaohs are discussed in this issue. Aidan Dodson explains how the decipherment of hieroglyphs enabled early Egyptologists to rediscover the forgotten story of Thutmose III and Hatshepsut, now two of the most famous of all the ancient rulers. Much less famous, but also hugely significant, was Senusret I. Wolfram Grajetzki celebrates the pharaoh’s achievements in transforming Egypt into the traditional pharaonic state we would recognise today.