How should we look after our historic towns? At Lincoln, English Heritage has been sponsoring a new way of assessing them, a project that will certainly be a world beater. Instead of just one research agenda for the town, there are now no fewer than 550 research agendas, arranged by era and each covering a small zone of the town. The book that outlines the new agendas is accompanied by a CD Rom for computers, on which all these Research Agenda Zones are mapped. This is the way that urban archaeology should be done: let the world take notice.

The project involves a complete re-assessment of Lincoln’s history, so here we look at four separate aspects. Was there anything at Lincoln before the Romans came? Who was the owner of the huge villa just outside Roman Lincoln? Then, medieval Lincoln: why did it rise so early and collapse so early too? And finally, the remarkable resurgence of Lincoln in the late 19th century to become a major industrial centre.

Who would have thought that a new Roman emperor would be discovered? His name was Domitianus II, and he was probably emperor for a very short period around 270 AD at a time when the Gallic provinces had broken away and had their own emperor. All this is based on a single Roman coin found by a metal detectorist, and Ian Leins of the British Museum has worked out the full story.

Kintore, near Aberdeen, has long been known from aerial photography as the site of a huge Roman temporary camp. Left behind after Agricola’s attempt to conquer Scotland in the 80s AD, it is now being swallowed up by a new housing estate, but archaeological excavations in advance found that the Roman temporary camp was the least of the features. There were roundhouses stretching from the Bronze Age to the Pictish period, – to say nothing of exotic Neolithic rituals.

The spire of Salisbury cathedral was for long the tallest structure in England. Inside it is an elaborate scaffolding, left behind to provide permanent access. But what is the date of this scaffolding? A long programme of tree ring dating has provided some interesting answers.

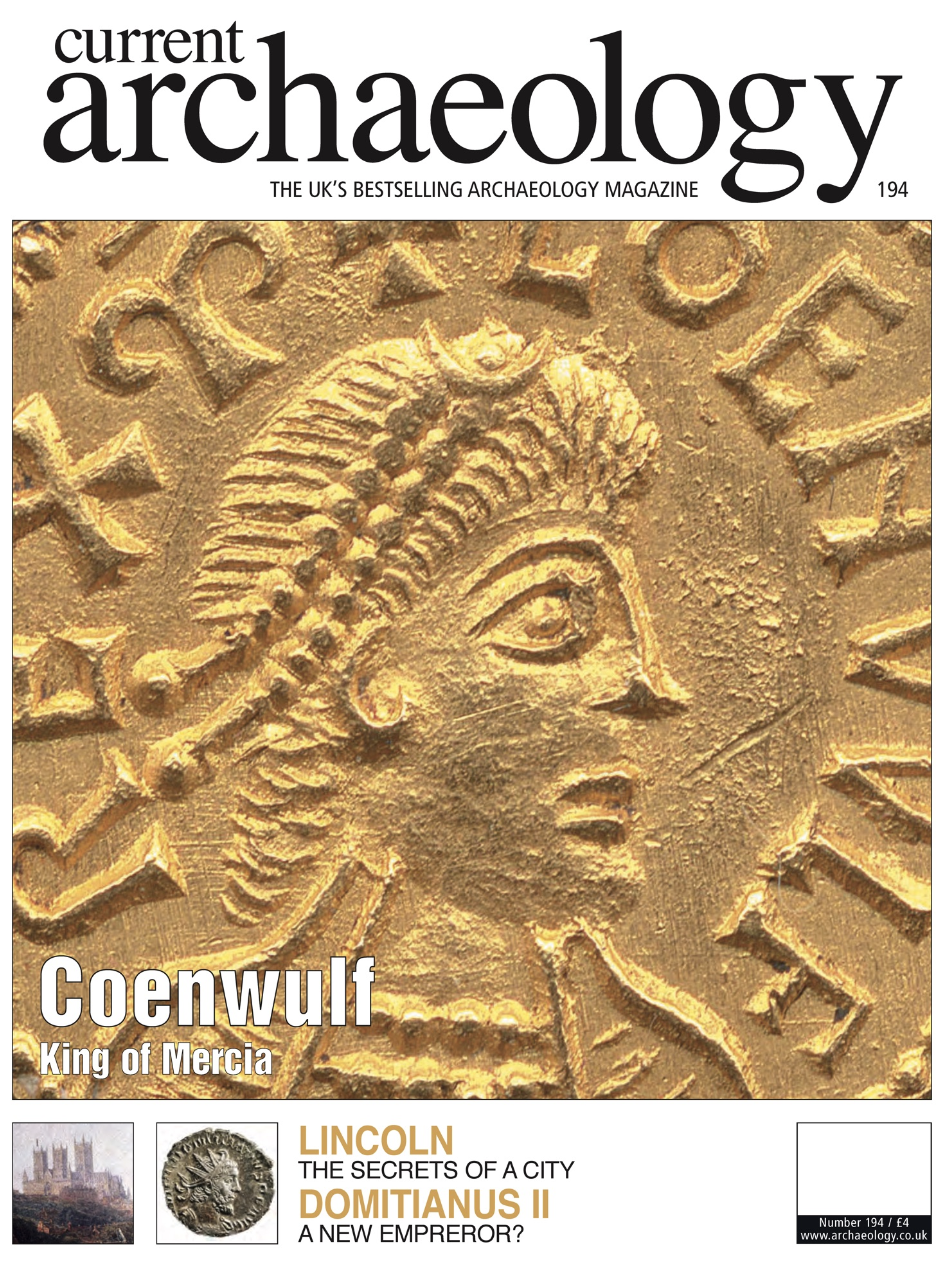

News items include a second magnificent gold coin, this time of a little known Saxon king, as well as the opening of two new museums at Piddington and Cirencester. But who was the rich lady at Cirencester, and how did she display all her wealth?

It is satisfying in this issue to be able to cover Lincoln so fully. We do not always sing the praises of English Heritage – or of those who slave in the bureaucracy of archaeology – but here they really have demonstrated that England, for once, really does lead the world!