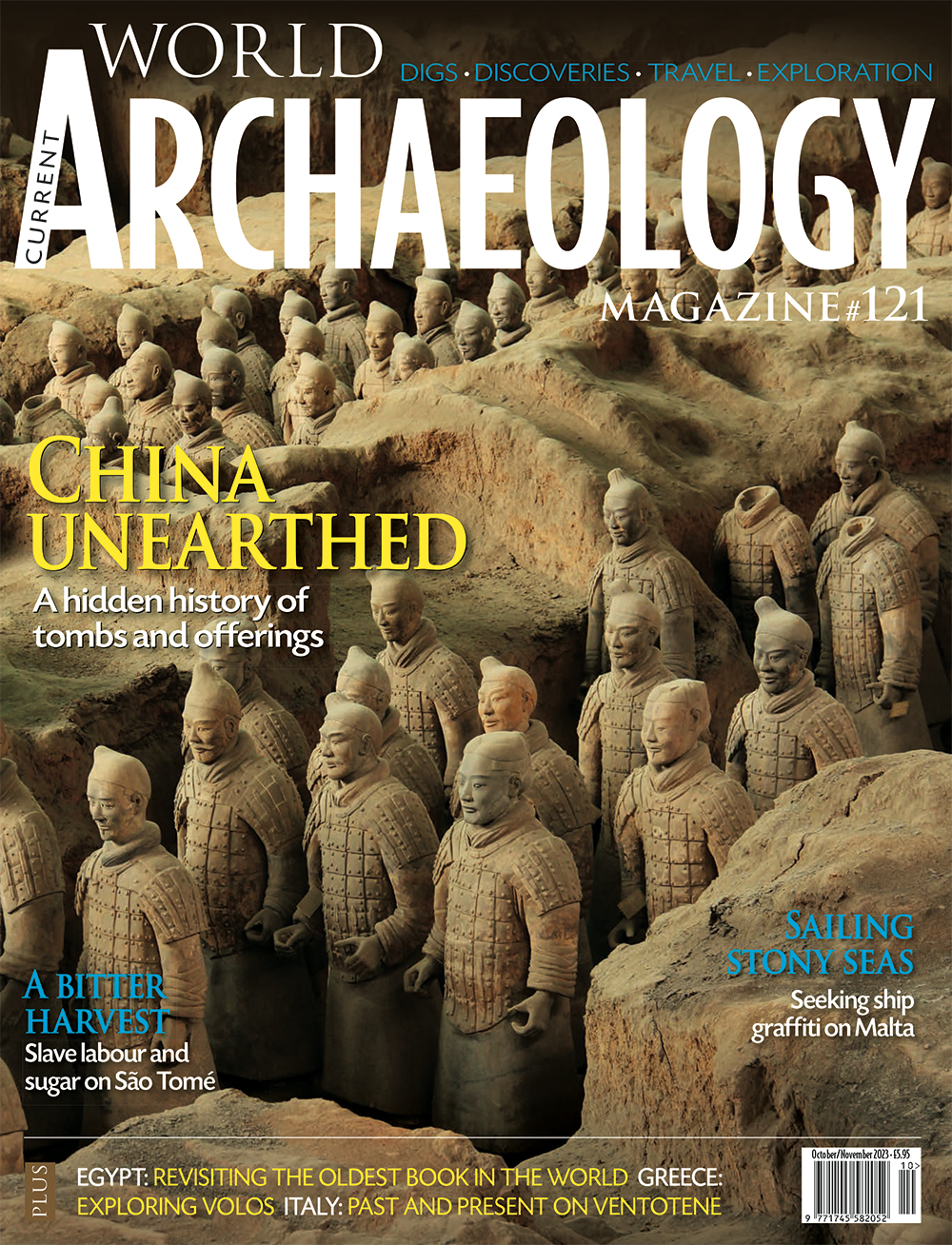

It started with the soil. The thick yellow loess that blankets much of northern China proved perfect for building city walls and platforms supporting timber buildings. Tombs could also be dug deep into this earth without causing it to collapse. It is within such tombs that many of the most astonishing trea sures to survive from ancient China have been found. Because the dead were believed to live on in these tombs, the objects accompanying them allow us to write biographies of the deceased. But these artefacts also tell a much wider story about how China it self developed over thousands of years.

On Malta, it is the sea that is crucial for understanding the rich heritage of the island. The enduring importance of maritime links is reflected in a wealth of ship graffiti, stretching from modern times all the way back into prehistory. Far from being crude doodles, some of these images are impressive compositions. But who was creating them, and why?

In ancient Egypt, we know that puzzling out the secret of life inspired Ptahhatp’s intellectual endeavours. The result was a text that survived – in varying states of completeness – to be collected by antiquarians or excavated from tombs. Ptahhatp’s work is now called the oldest book in the world, and sheds light on a pivotal moment for humanity: the birth of literature.

Founding plantations on São Tomé produced a lasting legacy, too, although in this case it was a bitter one. The model it pioneered for sugar production in a tropical environment using enslaved people came at a terrible human cost. The first archaeological project ever undertaken on São Tomé is currently examining this overlooked chapter in the shaping of the modern Atlantic world.

In our travel section, Richard Hodges contemplates the consequences of an archaeology of confinement on Ventotene, in Italy. Meanwhile, Martin Davies has gone off the beaten track to tease out the heritage of Volos, in Greece.